PLAINFIELD, Ill. — The way Marcus Mooney saw it, he wasn’t just selling hot dogs — he was selling experiences.

In addition to the classics — a cheese dog and a chili dog — his restaurant, Frank’s Night Out, served hot dogs topped with more exotic ingredients, like a “Surf & Turf Dog” featuring crumbles of garlic-basted Maine lobster.

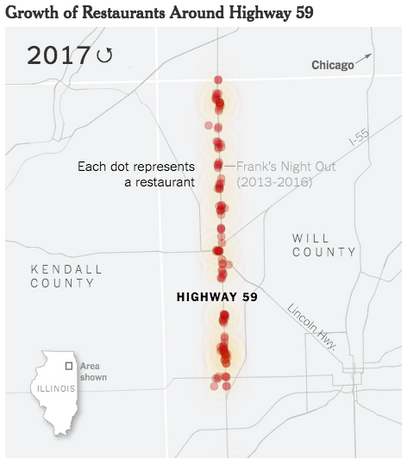

But the hot dog experiences Mr. Mooney offered were just one choice among hundreds for hungry motorists seeking a quick, inexpensive meal on this restaurant-laden stretch of Illinois Highway 59. His sales dropped. After opening his restaurant in 2013 and putting in seven-day work weeks, Mr. Mooney shuttered it last year.

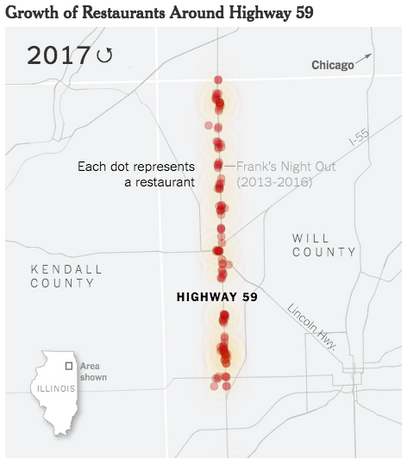

“There becomes a point where there’s too many choices,” Mr. Mooney said recently. “The more restaurants that opened up, the more it took away from business for us.”

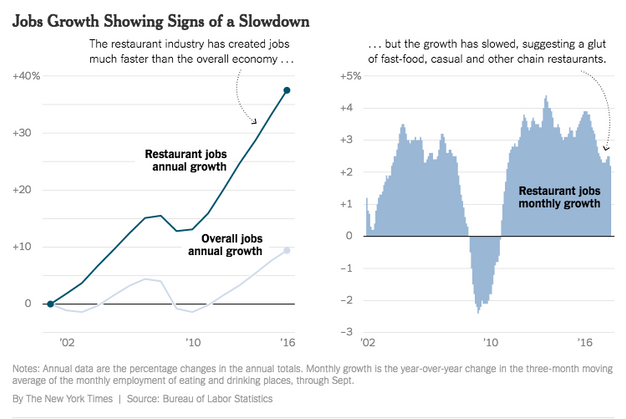

After a prolonged stretch of explosive growth, fueled by interest from Wall Street, experts say there are now too many fast-food, casual and other chain restaurants.

Since the early 2000s, banks, private equity firms and other financial institutions have poured billions into the restaurant industry as they sought out more tangible enterprises than the dot-com start-ups that were going belly-up. There are now more than 620,000 eating and drinking places in the United States, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the number of restaurants is growing at about twice the rate of the population.

That trend is evident on a more local level here in the sprawling suburbs southwest of Chicago, where the population is growing fast, but the number of restaurants is growing even faster. Twenty years ago, Mr. Mooney would have been competing against about 600 eateries in the region; by the end of last year, that number had more than doubled.

“Everybody thinks their brand has what it takes to succeed in the marketplace,” said Victor Fernandez, an industry analyst with TDn2K, a Dallas-based firm that gathers data on the chain restaurant industry. “You look at a location that looks good, but everybody is looking at the same place and they all come in, and the result is you get oversaturation.”

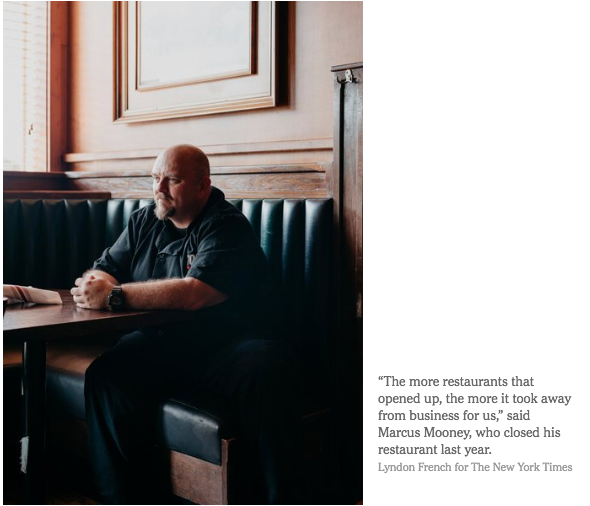

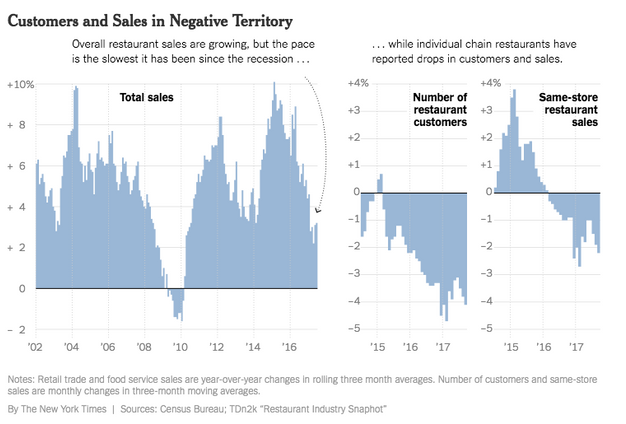

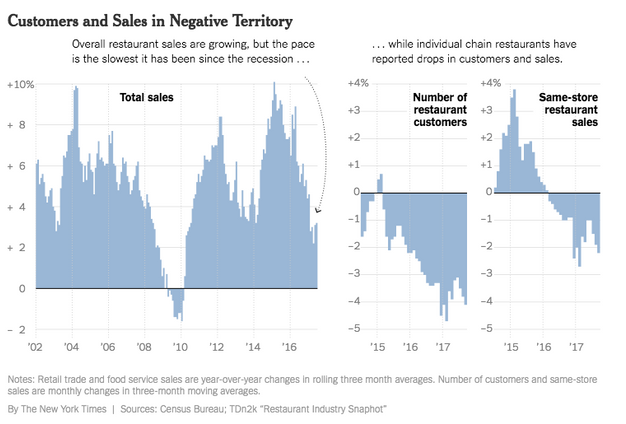

The glut of restaurants has increased the pressure on individual restaurant owners. Industry sales are up nationally, but growth has slowed to the lowest rate since 2010.

Customers continue to spend a large share of their food budget in restaurants, but they’re spreading the money across a larger number of establishments, so profits are split into smaller individual pieces. Yet the industry — particularly chain restaurants — continues to expand, a strategy that both masks the problem and makes it likely that more places will falter.

Sales at individual chain restaurants, compared with a year earlier, began dropping in early 2016, analysts reported. A majority of restaurants reported sales growth in just four of the last 22 monthly surveys from the National Restaurant Association. Before that, most restaurants had reported growth for 20 consecutive months, from March 2014 through October 2015, the survey found.

As Americans work longer hours and confront an ever-growing array of food options, they are spending a growing share of their food budget — about 44 cents per dollar — on restaurants, according to food economists at the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

But while consumer demand contributed to the restaurant boom, it was changes on Wall Street that really fueled the explosion. Chains like Del Taco, Papa Murphy’s and others began attracting money from private equity firms, and banks like Wells Fargo and Bank of America saw lending opportunities in the restaurant industry.

Those developments complemented each other well. New fast-food investors wanted to rely less on owning restaurants, and offloaded many company locations to eager buyers who came with bags of cheap money from the banks. The investors could then count on a steady stream of franchise fees and royalty payments — buffers against overall sales declines if, say, the market ever became oversaturated. And they didn’t have to worry about actually operating the restaurants.

Franchisees pay for the right to operate a McDonald’s or a Subway, following rules that dictate everything from what type of taco to sell to where to buy iceberg lettuce. They take on the risks and costs of running the restaurants, in exchange for the marketing muscle and name recognition these big companies provide. While every Dunkin’ Donuts or Taco Bell may look the same, dozens and sometimes hundreds of independent owners can operate most of the restaurants within a single brand.

But some franchisees say they’re being pressured to open too many stores as food companies push for new revenue streams. Buying an existing restaurant, for example, may mean agreeing to build 10 new ones.

“They want us to sign aggressive development agreements,” said Shoukat Dhanani, the chief executive officer of the Dhanani Group, which owns hundreds of Burger King and Popeyes restaurants. “I didn’t see that even five years ago.”

The shuttering of restaurants could have a major impact on the labor market. Since 2010, restaurants have accounted for one out of every seven new jobs, and many restaurateurs complain that it has become increasingly difficult to hire and retain workers. In Muscogee County, Ga., a former textile center, the Labor Department reported an overall decline in employment of 2,000 jobs since 2001 — but a gain of 2,700 restaurant jobs.

Those positions could be in jeopardy if sales continue to fall and force more restaurants to close. Over the summer, the parent company of Applebee’s announced it would close more than 100 locations. In 2016 Subway, the nation’s largest fast-food chain by location count, closed more locations than it opened, the first time in its history that had happened.

“Year over year, we are seeing chain restaurants grow at twice the rate of overall population growth,” said Mr. Fernandez, the TDn2K analyst. “We believe now there are probably too many restaurants and too many brands.”

In this business environment, restaurant owners are often risking their personal fortunes when they open a Pizza Hut or create their own idea for a restaurant, like Frank’s Night Out.

Melissa Arcache also plowed her life savings into her dream of running a successful restaurant. She now owns three branches of Bahama Buck’s, an island-themed frozen dessert chain decorated with surfboards and novelty mileage signs listing the distance to Bermuda and the Bimini Islands, in the Houston area.

Even before Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, Ms. Arcache was struggling. Sales in August were down 10 percent from last year, and business fell further after the storm. She looks at all of the competitors opening up shop nearby and wonders what she can do.

She said she doesn’t have a Plan B.

“This is what we’re going to make work,” Ms. Arcache said during an interview at her store in Houston, which was recently vandalized, leaving behind dents in the walls she has yet to patch up. “This is what’s going to feed my future kids and hopefully get them through college,” she said.

Mr. Mooney also put his life savings into his restaurant, Frank’s Night Out, only to see it fail. His personal life suffered, too — he was married when Frank’s opened but divorced by the time it closed.

He now works as head chef for a company that owns a brewery and restaurant in the same strip mall where Frank’s Night Out was located, and passes by his old restaurant on his way to work.

Transformed into a beef and gyro shop, the new establishment sells one of the items he created, a hot dog wrapped in bacon and topped with macaroni and cheese, lettuce and tomatoes. It even has the same name — the “Deep South Dog.”

At first, Mr. Mooney said, he felt relief when he looked in and saw few customers. “It allows you to think that the failure of it was not you,” he said.

But nine months later he’s rooting for the new restaurant to succeed.

“Now it’s kind of like, oh, man, I’m glad people are going in,” he said.

Link to original article: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/31/business/too-many-restaurants-wall-street.html